Today in New Haven there’s going to be a little book party

for my book on Bob Dylan. And some local musicians will be taking a stab at

some Dylan songs. So I figured I’d feature a Dylan song done by someone else. I

wanted it to be a woman, since that’s more infrequent than it should be. And

the one that came to mind, naturally, was “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again” as recorded by Cat Power for the soundtrack of Todd Haynes’ Dylan-inspired knock-off, I’m Not There

(2007).

That title of the film comes from what was once a very

obscure Dylan song, but it occurs to me to think of it in terms of the words

attributed to Christ: “wherever a few gather together in my name, I am there.”

So, maybe in a sense, when we gather together in Dylan’s name, he’ll be there.

In spirit.

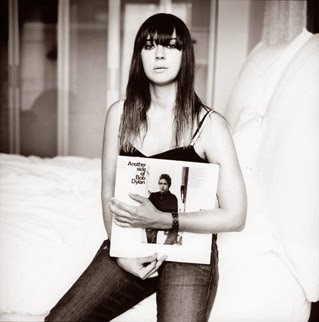

Cat Power’s cover was a natural choice because it’s so close

to the original and yet bears the hallmarks of Chan Marshall’s conversion (for

her LP The Greatest) to a bigger band

sound. The horns give it a punch that cross the song’s carnivalesque tendencies

with something a bit more Dixie-ish. Fitting since the song is ostensibly about

being in Alabama while pining for Tennessee and Marshall hails from Georgia.

She “restores” (in a manner of speaking) a southern twang to the song that

Dylan doesn’t go for but which is there somewhere in the background. It’s got

those overtones.

Marshall changes the first person pronouns to third person

masculine pronouns at key moments when, it seems, she doesn’t want to take

credit for what’s being described. So “The ladies treat him kindly / And

furnish him with tape / But deep inside his heart / He knows he can’t escape.”

I guess it’s OK that she still wants us to think of Dylan as the person to whom

this happens, but it is selective, since she’s willing to be the first person

speaker most of it: “And like a fool I mixed them / And it strangled up my mind

/ And now people just get uglier / And I have no sense of time.”

Actually what it comes down to is that she goes for

masculine when ladies are involved, lest we think, I guess, that the ladies

treat her (Chan) kindly or that she would like to escape their ministrations.

Likewise she’s not the person to visit Ruthie “in a honkytonk lagoon,” though I

have to say that her delivery of Ruthie’s words have even more sly insinuation

than Dylan’s does: “Your debutante just knows what you need / But I know what

you really want.”

And that’s the way much of the song goes. Marshall is in

full command of the lyrics, as if she had written them herself (or has sung

them so many times she owns them). She knows how to mimic Dylan without mocking

him—her vocal, like most on the soundtrack, is reverential and referential,

pointing us to Dylan’s own recordings without seriously altering the songs. The

one notable exception is Iron & Wine’s cover of “Dark Eyes,” which I almost

chose for today. But of all the reverential treatments, Marshall’s is one of

the best. She’s got great musicians with her and they make the song feel more

upbeat than the original does (it does, but it’s got that late night feel the

whole album has), more alive and popping. And with Marshall’s tongue-in-cheek

vocals, every verse keeps us moving through a range of scenes that, mostly, are

embarrassing or silly or vaguely ominous, but never quite the mind-fuck of some

of Dylan’s phantasmagorias.

This song always struck me—my first hearings of it

were out of the context of Blonde on

Blonde (one of Dylan’s most consistent post-acoustic albums in terms of its

sound and its themes) on Greatest Hits

Vol. 2—as one for the guys, by which I mean “the boys in the band.” It’s a

song about the peculiarities of the life on the road where one day you’re in

Memphis and the next day you’re stuck in Mobile, wishing you were still in

Memphis. That’s one way to construe the “blues” of the song, but it could

almost be a band name: so you’re a singer stuck in Mobile with The Memphis

Blues again. In any case, the singer of the song always struck me, more than in

some of Dylan’s adventure songs, as Dylan, in the sense that the characters—the

French girl, Ruthie, Mona, the senator, the preacher, grandpa, the ragman—are vaguely real,

often with the status of occupations, which becomes so marked on John Wesley

Harding. There are only a few oddities, like the rainman and the neon madmen

and Shakespeare, that harken to the mood of “Desolation Row.” So,

compositionally, the song is on a continuum from the latter song to the songs for the

next album, but without the visionary sense of “Row” or the moral allegory of JWH.

“Stuck Inside” is one of those weird psychic distress songs like “On the Road

Again” or “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry” or “Outlaw Blues”

gone through the elongation of experience that makes people just get uglier, and

come out the other side.

Marshall, who has enough heebie-jeebies about performing to

derail herself regularly, seems fully steeped in the mood of this song, willing

to ride a version of dylanesque androgyny as far as she can go. And it takes

her far. My favorite line in her version is “he built a fire on Main Street”—she

says it with such crisp enunciation, almost a send-up of Dylan’s slurry diction

and its tendency to odd emphases. Hers are odd in their own way and she seems

thoroughly at home in Dylan’s shoes on this one.

You see you’re just

like me / I hope you’re satisfied.

No comments:

Post a Comment