Today in 2011 Clarence Clemons of the E Street Band died.

Earlier this week, it so happened that I saw on cable a concert of Springsteen

and his band from 2000. Watching Clemons, knowing he’s gone, had a certain

impact, and I got a bit misty when they played “If I Should Fall Behind” and Clemons

took the mike, along with Patty Scialfa, Nils Lofgren, and Miami Steve Van

Zandt, in a close shot with Bruce. The show was full of the camaraderie of the

E Street Band, though at a considerable remove from when I saw them on the tours

in 1978 and 1980. Which is a way of saying that I go back quite a ways with

that band and Bruce, back to long before their big money-making hit album Born in the U.S.A. (1984).

I more or less stopped being an automatic buyer of

Springsteen LPs after Tunnel of Love

(1987), though I’ve kept up, sorta. The Seeger Sessions in 2006 got me

interested again, though not to the same degree. While we were watching the

concert, I was reading aloud through Rolling Stone’s list of 100 Best Songs by

Springsteen, and while I disagree with the rankings and some of what’s on

there, I feel that almost any song of Springsteen’s that needs to be on there

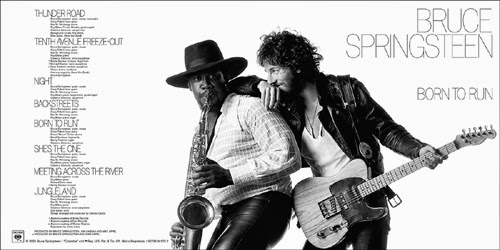

is. After giving it a bit of thought, I realized that today’s song, from Born to Run (1975), is most likely the

song I’d pick as my #1 Springsteen song—partly from how I felt hearing the band

launch into it in the concert. “Backstreets,” which they also played, was

another strong contender, but I have (maybe) more reason to pick this one.

I should say that

Springsteen was a major touchstone for me from 1977 to 1980, after that less

so. The latter fact due in part to the endless earnestness of his songs, and the fact

that, no matter how big he got, he couldn’t drop the effort to romanticize grease

monkeys and their girls, the working guys and homecoming queens of some

perpetual high school date night. As someone who more or less detested high

school and grew up around the types who think jobs and family and houses are the be-all and

end-all, I had to both respect Bruce for his ability to find ways to poeticize

such lives as well as look askance at his many redundant themes. How many times

does someone “cross the river to the other side” or spend time monologuing from

behind the wheel of a car?

But put all that quibbling aside for the moment. “Thunder

Road” is one of Springsteen’s big, sweeping, grand mini-epics about the flurry

of romance when a guy—just your average Joe, Bruce-style—realizes that he can’t

live without “the girl.” And there’s only one, even though she sounds like

legions of regular girls who need to separate themselves from some kind of stultifying

home environment—either it’s not cool or it’s too constraining or it’s just not

good enough for you, babe—and ride off into the sunset in the mean machine of

the guy with the most charisma and machismo on the block. It’s the great

American fantasy of boy and girl off to see the Wizard, so to speak. Given that

this basic scenario gives rise to the likes of Clyde Barrow and Charles

Starkweather as “romantic heroes,” it’s not surprising that Bruce eventually

gets around to a very dour and powerful song about the latter serial killer—and

his thrill-ride girlfriend—called “Nebraska.” But that’s the dark side of today’s

song, so to speak. After all, this one says “It’s a town fulla losers, I’m

pulling out of here to win”—and the way Roy Bittan’s piano leads the crescendo after

Max Weinberg’s drum roll is one of my favorite moments in all of Springsteen,

and it keeps up, with the piano doing wonderful fills as Clemons’ sax, blended

into Jimmy Iovine’s wall of sound, keeps pumping like a maverick heart, all going on for

a full minute at the song’s stirring conclusion.

For all the irony I can’t help but feeling—“all the

redemption I can offer, girl, ‘s beneath this dirty hood”—at times, the song

boasts many great passages that show Springsteen to be fully in command of his

idiom: “You can hide ‘neath your covers / And study your pain / Make crosses of

your lovers / Throw roses in the rain / Waste you summers praying in vain / For

a savior to rise from these streets.” If that doesn’t give a nicely worded spin

to the usual bored girl at home looking for excitement—and one that is also

shy, pained, and maybe even Catholic—then I don’t know what. And the opening harmonica

is so plaintive but resounds with “call of the road” excitement as the

singer speaks of Roy Orbison singing for the lonely, a way of indicating,

early, that this is all about the redemption via radio, of songs that sweep up

the spirit into subtle longings. Since high school, kids, and before.

But it’s more than that. This is about the doldrums after

high school ends and how do you make a go of it then, of having a social life. “So

you’re scared and you’re thinking that maybe we ain’t that young anymore.” That’s

the part that got to me in 1978, a year out of high school, and even more so a

year later when I put it at the start of a tape I gave to an older woman I knew—many

years out of high school and college—as a kind of gesture toward the kind of

romance I hoped she was still willing to feel. That she happened to be named

Mary like the girl in the song (the most common girls’ name in the U.S. for

decades) is just one of those things. Certainly the idea that I was asking her

to leave her home for the front seat of my car was absurd. I didn’t have a car

nor even a driver’s license. Like I say, the terms of Springsteen’s fantasies

are rarely mine, but I’d be lying—and denying something in me akin to his

vision—if I said I didn’t see my situation, or at least its feeling, mirrored

in some of his songs, particularly this one. That song became one of those

great “running away from it all” songs and that was important then.

In that Rolling Stone

list, the write-ups for the songs tend to speculate about the real life sources

of some of Bruce’s lyrics. I never do that. I really don’t care who a given

artist is sleeping with, slept with, or would like to sleep with. I’m much more

concerned with my own erotic life. And that means accessing songs through the

kinds of fantasies, and sometimes experiences, that my own life provides and

which often find answering reflection in songs I like to hear. It’s much less

the case now—soon to be 55—that such things happen, but back then, when I was

getting to know this album and Springsteen’s next, Darkness on the Edge of Town

(1978), it wasn’t so much that the songs “spoke for me” or even “to me,” but

that they spoke in a way that was plausibly “like” the place I lived in then

(New Castle, Delaware, with its closeness to New Jersey and to the seashore,

and to Maryland, as well as cities like Philly, and NYC and DC) and showed how

it could be done. Not that I ever wanted to write about truck stops and sock

hops and burger joints and cops and greasers and gangs and the heart-stopping

beauties you can sometimes find in the midst of it all. But when I was down by the

sea in Ocean City, as I am now, the world of Springsteen always came to mind, till I was 22 or so.

What I love most about this song is that it’s a long,

sprawling lyric and the song has no real chorus, though it moves from crescendo

to crescendo, constantly upping the ante, so that the big spike of “oh and that’s

alright with me” gets driven further by “we’ve a chance to make it good somehow

/ So what else can we do now” and then hits the spike from “the night’s

busting open” to “Thunder Road.” Then it

gets wound up further with “tonight we’ll be free / All the promises will be

broken” as the sweet talk of this importunate lover gets more excitable, more

demanding, but also more sure of himself. It’s a great monologue, full of male

desire and able to sketch the skittish attitudes of its object of desire so

that, whether or not either is our romantic ideal, they take shape for us and

the amazing arrangement of the song makes us believe in them, as Springsteen,

vocally, gives it his all in what is still my favorite of all his recorded

performances.

We got one last chance to make it real.

.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment