I was in 8th grade—13 years old—when Lou Reed’s “Walk on the

Wild Side” was released. That’s the

perfect age to be impressed by a song that features transgender characters, “giving

head,” and those “colored girls.” The

song is delivered in a dead-pan voice that was easy to follow but hard to

mimic. It was hard to mimic because

there was something in that voice—its owner’s self-awareness, his sure grasp of

what he’s talking about, and who he’s talking to—that chilled you, thrilled you

with fantastic visions never felt before.

He’s not talking to our parents—even though my parents were

exact contemporaries of Andy Warhol, the figurehead of the scene Lou’s

describing—he’s talking to all of “us.”

At one time, the “us” would have been called “freaks,” but that era of

the Sixties was already history. There

was nothing to unite someone newly turned a teen with any particular

group. I’m not saying “Wild Side” did it

for me; I wasn’t pining for the kind of scenes Lou was describing, or anything

like that, but . . . It impressed me,

left its mark. I imagine it did the same

thing to many who had never heard those kinds of characters and scenes so

forthrightly placed on Top Forty radio before.

Sure, there was The Kinks’ “Lola,” but that was so playful, whereas there was something a bit menacing in the

cold authority of Lou’s tone. Of

course David Bowie had already launched his androgynous alter-ego, Ziggy

Stardust. It wasn’t like this was coming

out of nowhere. One could even say that

this was the “sell-out moment” that someone like Warhol always dreamed of. Lou’s on the radio, singing about Candy

Darling—and the record is selling! Something

that was still “a scene” went viral, as we say today.

So I started reading “rock rags” more regularly, and there I

got glimpses of Mr. Reed. I’ll never

forget the image of him performing that accompanied a one-page story on

his album Berlin (can't find the photo online). This was 1973 and I was a fan of Jethro Tull

and Yes and, soon, Pink Floyd. Bowie was

still percolating on the edges for me, but maybe it was the Reed/Bowie

connection that made Aladdin Sane a

must-have record for me at that time.

But Lou . . . he was still a bit too-too.

Then came the Rock’n’Roll

Animal phase, when he looked like an anemic idol, a platinum greaser who

had served time in a concentration camp.

A camp concentration camp—because

by now Nazis were combined with the decadence of the cabarets of the Thirties

to produce a rage for an erotic image to inhabit the dreams of fetishists and

masochists flirting with fascism. I was still looking askance at Lou’s

posteuring, his stab at arena-rock that made everyone wanna-be cokeheads. Then, in 1976, an older friend turned me on

to The Velvet Underground Live ’69

(which was not released by Mercury till 1974, after Lou was suddenly “a hit”). My friend insisted that this was the live Lou

that mattered—not that rock anthem schtick of the Animal era. And I saw his point at once.

Live ’69 did

it. It gave me the Lou Reed that I would

treasure ever after. Those long cruises

with discursive strumming through great VU material—my favorite side was

comprised of “Ocean,” “Pale Blue Eyes,” “Heroin”—were not captured with

absolute sonic fidelity. The sound was a

bit thin, lacking in bass with the highs a bit attenuated, but the power and

passion came through. “What Goes On” is

revelatory, and “Sweet Jane” betters any other recording of it. There is some filler (it’s a double disc on

vinyl and even on CD), but, for the most part, this album is classic and one of

the great live albums from that era of live albums, c. 1969-70. Hearing the record sent me back to the VU

studio recordings. And my fascination

with a figure encountered there—the mercurial John Cale—sparked a connection to

Lou’s sometime bandmate that surpassed in many ways my interest in Lou. But we're talking about Lou now.

There’s no denying that everything that’s great about Lou’s

songwriting is on that first Velvets album: the lyrical Lou (“Sunday Morning”),

the bitter Lou (“Femme Fatale”), the caustic Lou (“Run Run Run”), the heroic

Lou (“Heroin”), the artsy Lou (“European Son”), the dark poet Lou (“Black Angel’s

Death Song”), the fascist fetishist Lou (“Venus in Furs”), the drug dude Lou (“Waiting

for My Man”), and even the cross-dressing Lou (“All Tomorrow’s Parties”) and

Lou-as-Andy (“I’ll Be Your Mirror”).

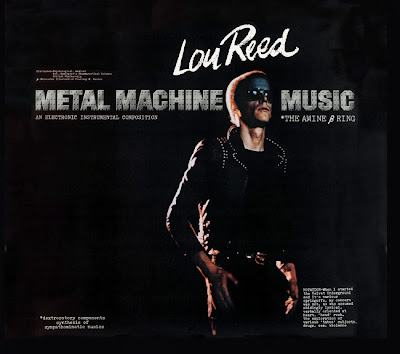

Some version of most of those personae fueled Lou’s work into the

Seventies, culminating, perhaps, in the “unlistenable” four-sided aural

apocalypse Metal Machine Music. Lou has said that he doesn’t know anyone who

has listened to the whole thing. I

did. All four sides, with

headphones. Stoned. So there.

But that was post-high school, 1977-78, and by the spring of

’78 Lou was inspiring praise in Rolling

Stone magazine for his latest incarnation: Street Hassle. And

deservedly so. I was ready for it

too. A major musical event for me in

that long first year out of school—at home with no direction home—was finally

getting around to Lou’s baleful Berlin. Here, retrospectively, I discovered that Lou

had put down on vinyl a masterwork back when I was noodling around with

extended sidelong sprawl, in search of the definitive concept album. For many, that was Dark Side of the Moon. Yet

Lou’s was more literary, more detached (he was clearly enjoying being the

scribe of those scenes, well, ok, maybe not enjoying, but he certainly had the

flair for it), and more generally applicable—it wasn’t about being in a rock

band, for starters.

Berlin is a skewered take on the hip life that so many were living

and the rest—the working stiffs—pining for.

And it let you know—whether you were initiated or uninitiated—what some

of the costs were like. It’s

relentlessly dark but—thanks, to a large part, to the wizadry of Bob Ezrin—it shines

with amazing aural clarity. It’s a

listening experience in the way that was true when The Beatles broke the mold

with Sgt. Pepper. From 1967 to 1973. Six years.

Judge for yourself.

So, Street Hassle. That first side was it. “Dirt” became kind of an anthem at the time.

A song about a song that was an anthem (“you remember this dude from Texas whose

name was Bobby Fuller? He wrote a song,

I’ll sing it for you, it went like this: ‘I fought the law and the law won’”),

it give us “the dirt” about people “who would eat shit and say it tasted good,

if there was some money in it for ‘em,” and it reminded everyone—yes, dear

listener/reader, even you—that we’re “just dirt,” the way Hamlet reminds a king

he may go a progress through the guts of a beggar, in the end. And the sound of the song is disheveled, full

of sounds that seem to ricochet around without adding themselves to what could

be called “an arrangement.”

Then comes “Street

Hassle,” a three-part mini-epic that showcases, in one view at least, a great

one-night stand; an OD; a wracked paean to lost love. At the center of the song is that OD’d “bitch”

who helps define what a “street hassle” is.

Lou’s been on that street too many times, perhaps. At least we’re willing to believe the voice in

the song has. It’s a song that shakes

you up because you have to make it cohere in your listening experience of

it. You have to live through its scenes,

listening, and come out the other side. It

more or less compresses Berlin into

eleven minutes, with the added benefit that it gives you that earnest “neither

one regretted a thing” line at the end of the first part, which, y’know, has to

make up for a lot.

So, by then—1978—I’m a Lou fan. He’s got the great early band LPs—that first

VU album just keeps getting better, and I recently got a re-release mono of it

that’s better than the old copy of it I used to have—he’s got the unforgettable

masterpiece (Berlin); he’s got the

varied moves of the rock chameleon (Rock’n’Roll

Animal and Metal Machine Music);

and now he’s got the wherewithal, past 35, to be in a mature phase—Street Hassle, followed by The Bells (1979) which likewise has a killer

side (Side A on Hassle, Side B on The Bells). “All Through the Night” and “Families” went

along, jabbingly, with where I was living at the time in my own attempt to get

gritty in the city (Philly, where I saw Lou perform at the Tower on the Hassle tour—and I can never forget him,

all buffed-up at that point, standing in a single spot pounding his fist into

his palm to the lone heartbeat sound that leads from Part 2 of “Hassle” into 3),

and “The Bells” spoke to a suicide that took place in my family at that

time. Lou’s dark side was coming up with

at least a side of good stuff every year (the other sides on those LPs are much

more hit and miss; can it be that I’ll ever listen to “Disco Mystic” with

fondness? Maybe, now that Lou’s gone).

“All Through the Night” and “Families” went

along, jabbingly, with where I was living at the time in my own attempt to get

gritty in the city (Philly, where I saw Lou perform at the Tower on the Hassle tour—and I can never forget him,

all buffed-up at that point, standing in a single spot pounding his fist into

his palm to the lone heartbeat sound that leads from Part 2 of “Hassle” into 3),

and “The Bells” spoke to a suicide that took place in my family at that

time. Lou’s dark side was coming up with

at least a side of good stuff every year (the other sides on those LPs are much

more hit and miss; can it be that I’ll ever listen to “Disco Mystic” with

fondness? Maybe, now that Lou’s gone).

“All Through the Night” and “Families” went

along, jabbingly, with where I was living at the time in my own attempt to get

gritty in the city (Philly, where I saw Lou perform at the Tower on the Hassle tour—and I can never forget him,

all buffed-up at that point, standing in a single spot pounding his fist into

his palm to the lone heartbeat sound that leads from Part 2 of “Hassle” into 3),

and “The Bells” spoke to a suicide that took place in my family at that

time. Lou’s dark side was coming up with

at least a side of good stuff every year (the other sides on those LPs are much

more hit and miss; can it be that I’ll ever listen to “Disco Mystic” with

fondness? Maybe, now that Lou’s gone).

“All Through the Night” and “Families” went

along, jabbingly, with where I was living at the time in my own attempt to get

gritty in the city (Philly, where I saw Lou perform at the Tower on the Hassle tour—and I can never forget him,

all buffed-up at that point, standing in a single spot pounding his fist into

his palm to the lone heartbeat sound that leads from Part 2 of “Hassle” into 3),

and “The Bells” spoke to a suicide that took place in my family at that

time. Lou’s dark side was coming up with

at least a side of good stuff every year (the other sides on those LPs are much

more hit and miss; can it be that I’ll ever listen to “Disco Mystic” with

fondness? Maybe, now that Lou’s gone).

The Eighties. After those albums with the dense aural elan came albums

much more funky and clean: Growing Up in

Public (1980), The Blue Mask (1982), Legendary Hearts (1983), New Sensations (1984) (here and there are glimpses of the old Lou: like the amazing title song

of The Blue Mask which fully revisits—with

a vengeance—the Lou of the first VU album . . . and for the razor slice of Lou’s

deadpan voice, listen to the line “watch your wife” on “The Gun”). Lou's got a great band including Robert Quine and Fernando Saunders. Lou got married! Lou's having fun! Lou's “Doing the Things We Want To” (a track

on New Sensations that always brings

a smile, with its unguarded tributes to Sam Shepard and Martin Scorsese), Lou's “Bottoming Out,” Lou's clean (“Last Shot”), Lou's in love (“Heavenly Arms”)

and finding out what being married is like (“My Red Joystick”) (I’d been with

the same woman for 5 years at that point, so seeing Lou in that territory was

right on), and by the time he got to New

York (1989), he's thinking of starting a family (“The Beginning of a Great

Adventure”) at 47. New York is one of those albums that no one but Lou Reed could

make. The muscular musical presence of that no-nonsense band and the pithy

little parables about the state of the nation as viewed from his beloved city are quintessential—my

favorite is “The Last Great American Whale” and its killer last line: “It’s

like my painter friend Donald says to me: ‘stick a fork in their ass and turn ‘em

over, they’re done.’” Nobody helps you

smirk at grim truth like Lou Reed.

Then came his other bona fide masterpiece. Paired again, Lou and John Cale came up with

an album of songs in tribute to their late mentor Andy Warhol. As someone who doesn’t genuflect at the name

of Warhol, who rather tended to abuse him for his “populist” art, I owe to Songs of Drella my softening toward

Warhol and all he represents (in every sense of that term). Lou and Cale create a portrait of Andy that

is so affectionate—but not sentimental—so knowing about the vanities and the

values of their hero, that it is truly touching. And how many albums in rock music are

actually touching? It’s personal in a

very public way, and that’s what makes it. Andy was one who fully understood how to be an artist of the public

gesture—and here Lou and Cale repay him in kind. They’re speaking his language all the way, not to turn it against him, but rather to showcase how deeply affected they

were by both the man and the artist. It’s

a great tribute, the kind of thing that artists often do for their fallen

influences, and it’s rather breathtaking how well it works. And, in 1990 when it came out, I was

certainly skeptical about anything in “popular art” working so well.

Then, I gotta say, I kinda lost track of Lou. I know he did that Poe thing (The Raven, 2003) and I still haven’t gone there. I’ve always been affectionate about some of Lou’s literary pretensions and the howlers I’d rib him about if I knew him personally (Lear wasn’t blinded, Lou, that was Gloucester, “wherefore art thou” means “why” not “where”), but, Delmore Schwartz or no Delmore Schwartz, I don’t know if Lou—the poet of plainspeak—is the one to catch the spirit of the poet of latinate locutions. Maybe it’s time I gave Lou a listen on that score, now that he’s gone finally to night’s Plutonian shore. Forevermore.

Good night, Lou

(March 2, 1942-October 27, 2013)