Continuing commentary on ‘15 Books That Made a Difference.'

7. The Great Gatsby, by F. Scott Fitzgerald (1925, American)

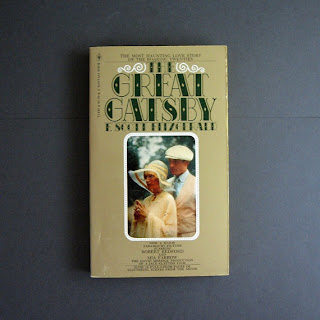

As with Ulysses, Gatsby is another work destined to become a ‘modernist classic.’ Unlike Ulysses, Gatsby had the distinction of being one of the few novels assigned for reading in my high school that I actually embraced as worthwhile. It was assigned in 12th grade, but I’d read it the summer between 9th and 10th when the film by Jack Clayton, starring Robert Redford and Mia Farrow, was released. It then became my task to see how ‘pure’ the film could be in terms of depicting the book. The film is remarkably faithful, which is one reason it’s not much admired as a film. Literature doesn’t make for good cinema. And yet I have a very real fondness for the film (Sam Waterston is the perfect Nick Carraway) and an even greater regard for the novel.

Still not ‘contemporary,’ Fitzgerald’s prose is closer to me than anything so far on this list. Joyce wrote Ulysses in the teens and twenties, but set the novel just after the turn of the century, the time of his own youth. Fitzgerald writes about the twenties in the twenties. My parents were born at the end of the twenties, and so this tale speaks of a time, pre-WWII, that they could recall and evoke for their kids. And the ash-heaps in which Wilson works smacks of the Depression era that would arrive after those flashy jazz era days that Fitzgerald is forever associated with. Then too, this is an American story, and one that, for many, is definitive: the rise to riches in pursuit of an elusive goal, to offset the notion that gaining wealth could be an end in itself, but also bringing to bear the sense that those from ‘below’ who aspire to the world of those ‘above’ will end badly because delusion, unlike privilege, is never its own reward.

What I primarily retain of this work is how the prose glows, how exact it is, and yet able to be lyrical, and comical, and thoughtful, without ever extending itself beyond the parameters of a ‘good read.’ It’s got the classic opening, the classic close, and depicts events that Nick the narrator seems to be ‘turning over in his mind ever since.’ As if there’s no quite satisfying way to sum up such longing, heartache, loss -- on Gatsby’s side, nor such indifference or self-involvement -- on the Buchanans’, nor such grotesque facts as the ability of the world they inhabit to cross paths, fatally, fatefully, with the world of the Wilsons.

It’s America, buddy, or at least the East Coast version. I give Gatsby, as a novel, great credit for acclimating me to the ‘idea of America,’ for literary purposes. For some, that sense of peculiar Americanness might come from something like Huckleberry Finn, from something with more of the mythic sense of space, and the tangled sense of race, that we recognize as irrevocably American, but let’s just say I’m more characteristically an Emily Dickinson shut-in than an expansive yawping Whitman, and for me America, to have any purchase on my imagination, must, as Gatsby’s father, Mr. Gatz, says of his son, Jay, rise to success in the East. Provincial? Certainly, but it’s a province, running from Boston to DC, that incorporates both the origins and in some sense the ‘last stand’ of this country. I don’t pretend to understand it, I just know it’s where I’ve always lived, and from that perspective, Daisy’s Louisville is indeed a mythic space out on the fringes of the known world (still East of the Mississippi) where a young ‘poor boy’ from North Dakota can find a vision to govern his life, and to make it all go down on Long Island rather than in Hollywood or LA is, perhaps, dated, but it’s also a factor that makes the book one of the essentials, to me.

(For previous entries in the 'Whatcha Readin?' series, see sidebar.)

1 comment:

The 2nd greatest book ever,

"My Life As A Small Boy"

by Wally Cox.

Stay on groovin' safari,

Tor

Post a Comment