Today is the 71st birthday of Mick Jagger. How best to pay

tribute? Say what you want, trash-talk all you want about Jagger, I’m inured to

it. The guy is—or was, anyway—truly iconic in my book. Jagger, as the frontman

for “the greatest rock’n’roll band in the world,” left his mark on my inner

life in ways that it might take a major psychoanalytic session to unearth. It’s

not the same as it is with the “heroes” whose work offers profound—or at least

provocative—explorations of the possibilities of language or of the

imagination. Though I believe Jagger is often a gifted lyricist, that’s not his

key contribution. There’s something in the entire Jagger manner—and that’s

where he often takes flak—that mesmerizes. Charisma? Sure. But it’s not just

that—most leaders of prominent bands, to say nothing of actors, have that. Jagger

has the capacity to be Mick Jagger. Which has always been an almost

unimaginable thing to be.

Granted, I’m speaking in the tones of my teen years into

early adulthood, when Jagger was at his height as a performer/singer/writer and

when I was still catching up on the Stones’ body of work. The period of their stuff

that is unshakably lodged at the pinnacle of rock’n’roll of my times is 1967 to 1972,

with a notable comeback in the 1977-78 period, ending with 1981’s lovely hodgepodge

Tattoo You. After that my interest is rather spotty. But that’s OK. By then,

things had changed, changed utterly (well, sorta) and a rocker of the likes of

Jagger in his heyday was not so desirable. But to speak, as I often do, of the

late Sixties/early Seventies—and the late Seventies, when lots of their music

from that time was coming home to roost, for me—is to speak of the

Jagger Era.

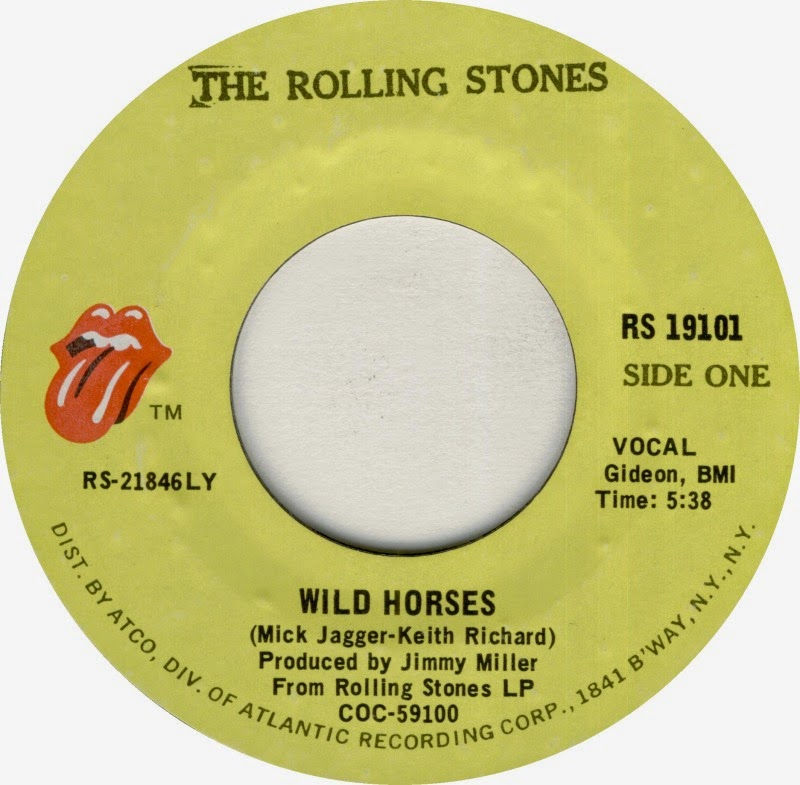

Today’s song is a case in point. It was on the radio in

the Summer of 1971. That’s when I first knew it, bought the single, liked the

song. But the Stones got a big boost in interest, for me and for many, with

Some Girls, which was a key LP of the Summer of 1978. Thereafter the Stones'

work in the period I mentioned above would never be out of favor with me.

“Wild Horses” won out over “Far Away Eyes” as the song for

today. In the language of my personal mythology, that’s saying a lot. There are

some who may be interested in what today’s song means in terms of Jagger’s

personal mythology. About that I can’t say. He married Bianca in May, 1971, and the song

suits well the first year of nuptials, one might imagine, except the song

dates from 1969, and he didn’t meet Bianca until 1970. Whatever. The song is,

to my thinking, the most romantic in the entire Stones oeuvre, and one of

Jagger’s best sustained lyrics. As with some of Dylan’s best romantic songs, it’s

in the form of direct address to a woman, so it can be taken as a “my heart’s

on my sleeve” outpouring for the sake of sustaining a desired—but threatened—romance.

The opening line alone was enough to grab me when it was

released in 1971 when I was almost 12. “Childhood living is easy to do.” I was

already one of those kids who considers himself retrospectively, which is why I

loved E. A. Poe’s “Alone” so much. It was possible even then to see myself “getting

over” childhood. By the time the song became a key song on a tape I made for my

next prospective romance (in spring 1979), childhood was long gone. And, as it

didn’t in 1971, “Graceless lady, you know who I am / You know I can’t let you

slide through my hands” carried a lot more urgency. Not sure about that “graceless”

bit, except to say it suggests the need for grace. Finding grace, let’s say, is

a way of saying “we’ve found it” in each other.

Key to me, then, was the “you

know who I am” part. My view being that lovers know one another, implicitly.

What no one else sees in you, your lover sees. For Mick, it might have

something to do with his fame and so on, but I give him credit for, in this

lyric, sticking to a close study of the kinds of heartache found not only in

love that doesn’t work out, but in love that does. The feeling of the song is

of the immense difficulty of living up to what a love demands of the lovers. It

would be much easier not to give a shit. And that’s where the “you know I can’t

let you slide through my hands” comes in: she might say, “go your own way and I’ll

go mine”; he says, “I can’t let that happen.” If sincere, he’s saying this one

counts and he can’t let her get away.

The second verse, about her “dull aching pain” (and listen

to how Mick—mixing country and blues and his own odd Brit inflection—sings “sufff-fur

ah-duhl AY-king pay-n”) and how she has shown him the same may allude to her

suffering through some other failed love and now trying to blow him off in the

same way. It’s sensitive! I know you’ve suffered, m’lady, and now you make me

suffer . . . also, the prospect of your having suffered makes me suffer. I’m

like total heart around you, y’know. And then, because this is tragic actor

stuff, he brings in a line I loved at once (I was a sucker for any use of theatrical

metaphors): “No sweeping exits or off-stage lines / Could make me feel bitter

or treat you unkind.” Graceful, that. The idea that big dramatic departures and

behind-the-scenes backchat can really poison an affair, but even if she’s prone

to such (a drama queen!) that wouldn’t get his goat. That’s a very big avowal

there. And clearly if she’s grieving a love that didn’t work out, then

promising not to be unkind is gonna score a point.

As a kid, I used to think maybe the woman was not well. That

these were the protestations of a lover who will be there to the bitter end. I

used to think that’s what the dull, aching pain referred to and the wild horses

that might drag him away. He’s not going anywhere, that’s the main point. But

even though I don’t quite understand my kid logic, the idea of mourning suits

the song's tone, which is mournful. So I won’t say I was wrong. Then again, maybe

it’s the speaker who hasn’t long for this world. In any case, the last verse

was the one that spoke the truth I wanted to maintain, in 1979:

I know I’ve dreamed you / A sin and a lie / I have my

freedom / But I don’t have much time / Faith has been broken / Tears must be

cried / Let’s do some living / After we die.

The use of “dreamed” as a double transitive verb is unusual. In

normal parlance, the line should say “I know you’re a dream” (“I’ve dreamed (of) you, or dreamed you (up)”)

but Jagger seems to say: “I’ve dreamed (for) you a sin and a lie.” In other

words, this coupling of her and him is “a dream” “a sin” and “a lie.” Doesn’t

sound too worthy of one’s trust. But that’s the nature of lovers’ protestations—which

are all dreams and lies, in one sense (the rational, trustworthy sense). What’s

more, the “sin” part may be because the “dull, aching pain” she suffers isn’t

from an ended affair but from one still going on. She might still “belong” to

someone else (which, by 1979, made this song seem kin, to me, with Lou Reed’s “Pale

Blue Eyes”).

A great line, worthy of a Dylan romantic song: “I have my

freedom, but I don’t have much time.” We know how Bob feels about his “precious

time.” But I don’t think this is just someone being impatient. This alludes to

that memento mori aspect of love. Like: if we had all the time in the world we

might never get around to—you know—doing each other, but since, like, time’s

short, why don’t we? The broken faith and tears part refers—as far as I’m

concerned—to the fact that she’s stepping out on someone in order to accept her lover (which is a

long-standing chivalric tradition and so Mick’s well within the bounds of

Knight to His Lady in this one). And

then the corker: “Let’s do some livvv-inggg afff-ter we diiiiiie.” And he holds

that like it’s his last breath.

That notion of living after death, some might say, refers to

the fact that they will find grace, be redeemed from their sins and lies, and

attain celestial peace, et cetera. Bunkum! sez I. What the line alludes to is

the notion of becoming celebrated lovers—like Romeo and Juliet, for instance—the

kind who live on after they die. In other words: let’s be legendary lovers, and

let’s live so that we’ll be remembered. Or, more colloquially: Let’s give ‘em

all something to talk about!

And while we’re at it, we’ll ride those wild horses someday.

And Keith Richards’ fills and solo on electric guitar are some of my favorite

note-for-note-perfect soulful-ballad embellishments in the entirety of rock

(listen to him on the final verse). And the twelve-string (Richards) with

acoustic (Taylor) sound is so stately and grand, to say nothing of how Watts

punctuates it all, especially the “after we die” line, and on that segue from

final solo into the restatements of the chorus.

“Wild Horses” is one of my faves for all time. 43 years old,

this summer. Thanks, Mick, and happy birthday, you old geezer.

No comments:

Post a Comment