Earlier this month—the 9th—marked the 25th anniversary of the

fall of the Berlin Wall. And in Chicago, since September, there’s been an

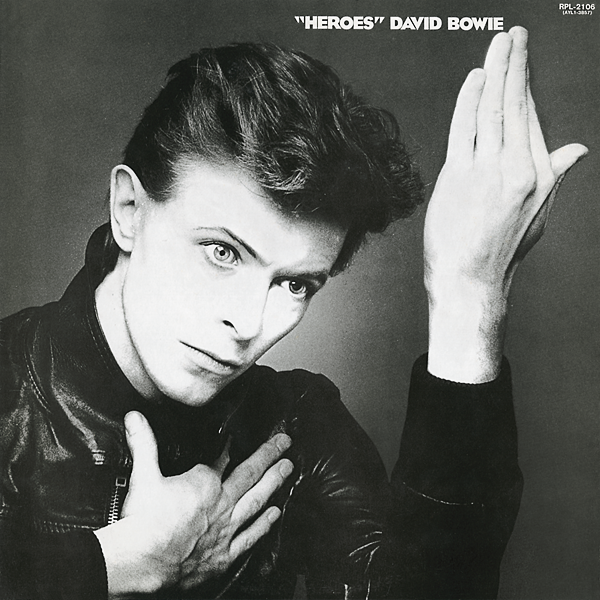

exhibit at the Museum of Contemporary Art called “David Bowie Is.” For me, one thing that David Bowie

is is the guy who put the Berlin Wall into a Top 40 song. “I remember standing

by the Wall / And the guns shot above our heads / And we kissed as though

nothing could fall.”

Bowie is—or was—a lot of things, and one thing, for certain,

is a kind of fetishized figure of self-invention. So much so that he

seems the first rock star who deserves to have his relics in a museum, not

simply because—the usual reason—of their “aura” of having belonged to a

creative artist, but because Bowie’s career has been an ongoing performance in

the art of making and re-making oneself for “the media.” All stars have to deal

with that, but few undertook it as the raison d’être of the entire enterprise.

Sure you can preserve Elvis’ jump-suits and guitar picks, but Bowie’s costumes

can rival big recent shows that celebrate fashion designers. And his videos are

as artsy as any commercial videos. And the trajectory of his career, the way it

sometimes follows, sometimes anticipates, sometimes leads what’s going down in

music and other popular arts, is instructive. He influenced a lot of people

working in what we might generally call “pop,” and he in turn was sort of the

poster boy for Andy Warhol’s view of what the artist of the Seventies should be

like. Warhol laid the foundation for all that in the late Fifties and early

Sixties. By the time he was producing The Velvet Underground, in 1966-67, he

had crossed into the territory that Bowie would thrive in. It was like Bowie

came along, bidden as the Messiah that the Baptist proclaimed.

But hold it right there—not Bowie, not David Jones. Rather

Ziggy Stardust. Ziggy was the Messiah. Ziggy was the uncanny, possibly

extraterrestrial, figure that fulfilled what the era pined for, after the death

of Jimi and the break-up of The Beatles, and the hedonism of the Stones, and

the various provocations of the Velvets. Bowie gave to Glam the tale of Ziggy,

then of Aladdin Sane, then of the Diamond Dogs, and then he got out, moving

back to R&B and torch songs before remaking himself—a “man who fell to

earth”—in a trio of albums from Berlin, with buddy Brian Eno helping out, and

Tony Visconti on the job. Low (1977),

“Heroes” (1977), Lodger (1979), together with the double live album Stage (1978) mark a highpoint in the

re-invention of Bowie. He became less an actor in his own theater and more

simply “just an artist.”

And today’s song is one of his best, graced with a wonderful

clarion guitar riff from Robert Fripp of King Crimson. Bowie was able to

marshal the avantist of the avant-garde of rock in this period. On this track there was

much use of moving about the studio and varied mic placement to create shifting

levels of recording, shifting feedback, and other tricks to make that dense

whine that the song builds up to, making Bowie sound more and more desperate

with his cry “We can be heroes, just for one day.”

Bowie et al. were more or less inventing the sound and

attitude that would take over the world of youth culture with the New Wave

babies coming on the scene. I sort of went into all this when I posted

about “Teenage Wildlife” back in January for the Thin White Duke’s 67th

birthday—picking another song with a great Fripp guitar part. So maybe those

are the ones I come back to most, as to some dreamtime when Eno, Fripp, Bowie

were all at work together, making the world safe for a crisp, cool, processed

lyricism. “I wish I could swim / Like the dolphins / Like dolphins can swim.”

Way back in 1977 when this song was first on the radio and I

was living my first post-high school fall, it didn’t immediately snap me up. I

suppose Bowie was “old hat” to me then. I preferred the lushness of Station to Station (1976) and was leery

of the ambient soundscapes of Eno, I confess. Bowie, to me then, wasn’t likely

to do better than the back-to-back pseudo-concept LPs The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders from Mars

(1972) and Aladdin Sane (1973). That

was high concept, that was camp-glam, that was starman drag, that was past

apocalypse repackaged as future shock, back when we really needed it. What more could he do?

The bid for radio in “Sound + Vision” or “Joe the Lion” seemed kind of flat,

barely worked-out. Minimalism, maybe, but so what? “Heroes”—with its “scare

quotes” before anyone used “scare quotes”—was different. It felt like a new

Bowie, or rather a look back, in elegiac mode, at what had been the charge of

best Bowie, now somewhat stripped of those filtering personae.

Maybe we’re lying /

Then you better not stay. That line

always resonated with me. It was an admission that all this bravado—“we can

beat them forever and ever”—might be mere fakery. But if not. If we “could

steal time” even “just for one day,” we could make it matter for a lifetime.

When I finally got around to getting the album—two years after it came out—that

was the message I was advancing. ‘Cause

we’re lovers / And that is a fact / Yes, we’re lovers / And that is that.

Enheartening that a man of 30, as Bowie was that year, could

still put so much passion into his evocation of lovers on the brink, lovers

standing for the pride of love—“and the shame was on the other side”—and for

the heroic dimensions the heart may acquire when it’s certain of its claim. And

I even liked the rather wry remark about what comes after, in the brief reign

of this king and queen:

You, you can be mean /

And I, I’ll drink all the time

No comments:

Post a Comment